| Artwork | Index | Editorial Writing | |

| Books | About | Links |

| Mary Heebner |

|

"Tuscan

Trails" Qantas, The Australian Way |

by Mary Heebner Photos by Macduff Everton |

|

|

Before taking a trip I read, rummage through clippings, pore over maps. However, in preparation for a walking tour through the hilltowns of Tuscany (with BCT Scenic Walking), I tried to locate Trequanda, read up on Castelvecchio, but was taken by surprise – according to several guidebooks, they simply didn't exist. This delighted rather than alarmed me because I knew I was in excellent hands. Our guide, Mario Acciai, is a home boy. When my daughter's godmother, Lise Apatoff traveled to Italy in 1976 to study art, Mario fell in love with this enchanting American girl, and they have made a fine life for themselves ever since, restoring an abandoned stone house above Florence, where they raise their son, 10 year-old Lorenzo. Over the years, Mario has taken us to waterfalls, to the family orchard to pick cherries, and through forests where men in wool berets and tattered brown sweaters filled their baskets with porcini the size of Frisbees. I looked forward to following Mario off the guidebooks and into his Tuscany. |

| As a young man, Mario, youngest of seven, was chastised for being a dreamer, singing and walking about the hills all day. He traveled to London to learn English, worked in a silver factory, was a roofer. Then he homesteaded. "For years Lise and I worked so hard, building our house, farming the land, raising rabbits and chickens, but a farmer makes no money. Now, can you believe it, they pay me to take people on walks, which is what I love most in the world!" We spent the first day in Florence with Lise, who had passed the rigorous exam necessary to be a certified Cultural Art and History guide for the City of Florence. She specializes in individually customized tours and is much in demand. Above all, Lise is an artist, so she knows that a child's easel painting or a Renaissance masterpiece begins with the stroke of a human hand. The entire group clustered about her, no one wandered off, as she led us through the city. She connects the dots in a way that kept us listening and looking.

Florence's paintings and buildings are a treasure-trove, and through her stories, Lise unraveled the threads of Florentine culture. "Andiamo, raggazzi, let's go, cowpokes!" intoned Lise, as we followed her down a sidewinding alley. |

|

|

There was the Duomo, huge as King Kong. Then, on the facade of the 14th century Orsanmichele, built as a grain market then converted into a church, Lise pointed to Donatello's sculpture of St. George, "people couldn't believe it when they saw how emotive and human Donatello's St. George was; women swooned," and "see the carved signs up there that stand for each of the guilds. Doctors, painters and spice-makers were all in the same guild; they were grinders – of pigments, medicines, and spice." Our group included two young women doctors, two sets of sisters, a plant pathologist, a linguist, retired radiologist and several teachers. Our ages ranged from late 20's to early 70's. After Lise's tour of the city her husband took over, asking that we meet at 9 the next morning, packed and wearing our hiking shoes. Walking has always helped me to get my bearings, internalize the map. It is the most intimate way of knowing a place. As we walked, my husband, Macduff, lingered to take photographs and I shuttled between him and those talking with Mario about the natural cultural history of the area, so I managed to see our routes both coming and going.

|

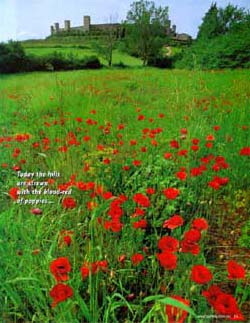

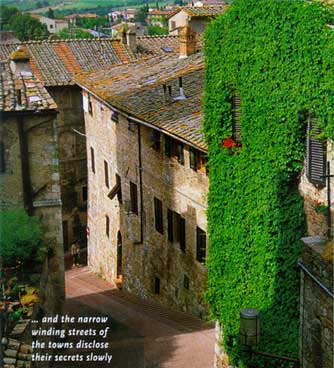

| The buildings and towns took on a life of their own as I learned that for over two hundred years, the rival parties of Florence (the Guelph noble-landowners who supported the Pope) and Siena (Ghibelline merchants, self-made men who supported the Holy Roman Emperor) engaged in brutal territorial wars which involved most of Tuscany – a bitter legacy handed down from father to son for generations. People lived under constant threat of invasion from their neighbors and were under the thumb of a punishing feudal system. The fortified hill towns that we would visit were built along strategic points. Florentines dredged stones from the fields to build their towers. Sienese fired the clay of their brick-red earth to erect theirs. Towers, churches and walls tumbled down and were rebuilt with such alacrity that one wonders how much the building guilds had invested in the belligerence. "When the Plague of 1348 decimated Italy's population the fighting and just about everything came to a halt." Lise had explained, "As life tiptoed back to a start, politics, economics, one's outlook and allegiances all had changed – there were possibilities again. Man was ready for the Renaissance." It was finally safe for the families to descend from the walled hilltowns to develop the marketplaces such as Gaiole and Greve in Chianti into expanding, thriving towns. The enterprise of wine replaced the enterprise of bloodshed. Today the hills are smattered with the blood-red of poppies and the narrow winding streets of the towns disclose their secrets slowly. Bruno, our bus driver, dropped us at Badia Passagiano, an abbey founded by Giovanni Gualberto in 1050. A cascade of bells sounded as we descended into the valley. A village dog joined the group and later sat with paws politely crossed as we picnicked in a small clearing among the pines. A few hours later we reached Montifiorelle, a medieval fortified village curled about a central church like a pastry snail. The town was empty. Most folks moved down to Greve generations ago, keeping the immaculate little town for summer retreats. Bruno appeared on cue, and after nodding at sad dog eyes we piled in the bus. For miles and miles we passed hillsides studded with olive and grape. The Etruscans, who inhabited Tuscany from 700 to 100 BC were the first vintners and olive oil producers in Italy. They knew that five hundred meters is the highest altitude for their successful cultivation and that having settlements along the hilltops was also advantageous for defense. Now these fields are literally rolling in lire. We were in the heart of Chianti Classico. I had asked Lise to tell me how the black rooster came to be the trademark of D.O.C. Chianti Classico. "One version is that the map of the Chianti region roughly resembles a rooster." Perhaps, if you have drunk enough of the vine, I thought. "The other version is an example of how the crafty Florentines overwhelmed the forthright Sienese: It was decided that in order to settle a border dispute, a rider from both Siena and Florence would gallop on horseback at the first crow of the rooster, and where they met would become the new boundary. At dawn on the appointed day, at the moment the black cock crowed in Siena, the rider took off, dumbfounded that the Florentine horseman arrived two-thirds of the way to his one-third. It was later revealed that the unscrupulous Florentines had starved their black rooster for three days and the poor thing crowed at 3am out of sheer hunger, signaling their rider to take off towards Siena." We based for four days at the Relais Fattoria Vignale, a converted 18th century estate in Radda, and site

|

|

where the Gallo Nero seal was created by the Notary of Chianti in 1924. Daily forays into the Chianti countryside always ended with a diabolically wonderful dinner, dispelling any illusion that one can lose weight on walking tours. Although I was with a group of twenty there were private moments, such as when I opened the door to a Romanesque church, San Donato in Poggio. A modest window curtained in white gauze let in a soft light behind a wooden crucifix. From two discreet speakers came an a capello man's voice chanting a Byzantine hymn. It was cool inside, with a faint smell of wax and flowers. In a small side chapel was a lovely baptismal font by Della Robbia. The serenity of the simple church lingered with me as I took off down the hill alone, filled with a lightness that lasted for hours. As we approached Piercorto Mario asked, "In English, what would you call a place that is smaller than a village, a little place?" The linguist correctly answered, "a hamlet," but my husband, who had once cowboyed quipped, "a one-dog town." As if on cue, a spotted dog lazily crossed the road. |

|

|

We shifted into different clusters, chatted, sang, forged ahead alone, straggled behind to photograph or simply smell the flowers. We usually had the trails, which Mario had scouted, to ourselves, only twice dodging hikers who blasted by at a Teutonic pace. We passed by an old man tilling his garden. Perched on a stool in front, an ancient woman meticulously folded blue gingham aprons. The man was her son. Each year she greets Mario with, "You saw me this time but I won't be here next year!" "She's been saying that for five years, now," smiled Mario, "she's 97!" Striking out from the hotel in a drizzle the next day, we took a verdant path that skirted the Villa Vistarenni and stopped for lunch at the Blu-Bar in the pocket-sized hamlet of Vertine. We cut through an olive grove down a path that led to the 10th century castle and village of Volpaia. The delight of this medieval hilltown is that within its ancient shell the Castello di Volpaia Fattoria had, in the early 1970's, painstakingly converted the interiors into state-of-the-art wine making and olive pressing facilities, gleaming with stainless steel and bright blue and white tiles. Emilia, our knowledgeable guide, led us on a tour which ended with an ebullient wine tasting. Usually after a day's walk, sleepy silence prevails, but tonight Bacchus smiled down on our bus enroute to the hotel, alive with chatter and laughter. "...la, la, la, amore misteerioooso ..."crooned Mario, putting us in a fine mood, oblivious that today's walk would involve fording a river, mucking through reeds alive with gargling frogs, and puffing up some hefty gravely inclines. As we browsed a cherry tree for the first ripe fruits, Joe stopped to listen to birdsong, "By golly, I don't think I've ever heard a cuckoo outside of a clock!" Mario told us that after a visit to Castello Brolio, where Bettino Ricasoli conjured up the 70% sangiovese, 15% malvasia and 15% canaiolo ambrosia known as Chianti, we would be leaving Chianti area for the gently rolling hills of Siena, and staying at a farmhouse. I only hoped that this farmhouse had hot running water for a shower. Siena's veneer of spring green belies an unyielding, erosion-fingered clay soil, that |

supports olives, sheep and wheat. Many of the brick farmhouses lie abandoned while the counterpart fixer-uppers in Chianti are going for California prices. Yet the seductive postcard images of Tuscany – the single flame of a black cypress against gently rolling hills smattered with wildflowers – comes from the Sienese landscape. Our hosts, Daniela and Duchio Pometti, welcomed us to La Selva – which has been in his family for a mere 900 years – with home-made wild boar sausage and crisp Trebbiano wine from the family cellar, before showing us to our individual cottages, complete with living room, kitchenette, bedroom and bath. Some farmhouse! Our windows overlooked the Sienese hills. Thyme, strawberries and roses grew outside our door. Dinner that night was like losing your virginity. You never knew food could be so good. Thirteen separate tastes, including tenderloin of Chianina beef rolled with spinach, pate, sage raviolis, roasted wild boar, rough-cut young artichokes with tarragon, and strawberry tarts; all bounty from their land. Vin Santo and grappa followed, and it was past midnight before we floated off to our room. Next morning we headed toward Montisi, and then to Pienza for a tour of the city. "Ciao, Mario!" hollered a swarthy Sardinian man from the top of his stairs. Many Sardinian shepherds came to Tuscany for the lush grazing over thirty years ago and they produce the most delicious cheese. Giovanni gestured for Mario, Jody and I to come see the pecorino he just had made. Steam rose from a cauldron of boiling water as he scooped out the sweet curds of ricotta, the residue left after the rounds of pecorino were formed and left to cure. Slowly the rest of the group trickled inside. Unfazed, he took a pile of paper plates, cleared his long table of bottlecaps and ashtrays, and invited all to taste the most comforting, heavenly flavor this side of mother's milk. We scooped up the warm ricotta with vellum-thin Sardinian "music paper" bread. This simple communion touched everyone. He showed us photos of his deceased sons set among a shrine of paper roses, and photos of the handsome racehorses that he had raised. We had few common words but shared the language of human warmth. After a lunch of salad and penne pasta in La Foce, Bruno drove us to Pienza, a town which was used in scenes from "The English Patient." Our guide, Andrea, had his fifteen minutes of fame as an extra. In the film, the statue that blew up in the middle of the piazza, killing several, was added as a prop. However, what was real in the piazza were the sandstone walls pock-marked with strafing of English bullets, as this was a German headquarter during World War II. "Stop!" we cried, as the bus drove past the hundredth field of wildflowers. This little mutiny made us late for the Pienza tour and in an instant half the group was forging a path through shoulder-deep mustard and poppy. "OK, follow me!" shouted Mario, holding a bunch of red poppies up like a tour leader's red flag. Below his raised arm he was entirely clothed in yellow and red wildflowers. Driving back to La Selva for our final night, Dr. Jane summed it up, "Between the cheese man and the poppies today, we're doing pretty good." Our final walk took us to the Abby Monte Oliveto Maggiore to see the stunning frescoes of the life of St. Benedict. Mario narrated the story of his life from riches to monastic life set during the plague years, and in the background we could hear the recessional music of a wedding in the adjacent church. We lunched beneath the wisteria-laced trellis of Ristorante La Torre then drove to Florence. Some weather was moving in. Those that were not napping were checking their maps, marking the places they had covered in these seven days. Driving past the circular signs with a red slash naming the town we are leaving, it was hard to believe we were only ninety minutes from downtown Florence. On my map, my thumb easily covered each day's walk, but within the inch is the mile, and within this small area I sang, walked, ate, drank and touched the heartbeat of Tuscany. Copyright © Mary Heebner 2000 |

|