| Artwork | Index | Editorial Writing | |

| Books | About | Links |

| Mary Heebner |

|

by Mary Heebner |

|

|

"Paintings on canvas are taken more seriously....They fetch a higher price.... Real artists use canvas.... I love the work but, canvas is so much more, well, substantial." I've heard it all, but still, it is paper that makes my heart beat. Each type of paper takes pigment differently. Every tear can reveal a white edge or a thin trail of fiber. I love the sound of paper, autumnal crackle or cottony whisper, and the weights of paper, sculpturally dense or thin as rain. I am not a papermaker, but a devoted amateur and I have had an affair with papers for nearly three decades. Paper responds, wrinkles, bleeds, shrinks or lays perfectly flat – a dynamic much like a stimulating conversation in which paper, pigment and brush are the mediums of exchange. It is up to me to coax something intangible from the process of making a whole out of a handful of parts. As a student at the College of Creative Studies, University of California at Santa Barbara in 1970, I painted in oils on canvas for my art classes and made little books illustrating the poetry of Yeats, Eliot, Lawrence, etc. for my Literature courses. In 1973, pregnancy prompted me to work exclusively with fumeless water-based media on paper. I entered UCSB's Graduate |

| program in 1975. Collage artist William Dole was my mentor. Paper continued to be infinitely more tractable than canvas to the nuances of color and texture, light and depth. Instead of regarding the ground as a neutral surface on which to make a picture, surface and image became two inseparable parts of a whole. I tore fragments out of my larger watercolors because they seemed to convey an essence that the overall piece lacked. I puzzled these shards of paper together and found that making collages was far more surprising and engaging than painting. By the end of 1977, I was working solely with collage, using water-based paints, powdered pigments, fabrics, and a variety of papers, some of them handmade. During trips to the US Southwest, I gathered oxides and ochre from the mountains and began to burnish earthen pigments into rag paper. I painted abstractions from rock formations stained with desert varnish; oxides that leeched out of sandstone formed during the Triassic. I continue to use powdered minerals, pigments and handmade papers today. I refer to maps, geology, and the art and myths of antiquity, probing the connections I find among human and earthen, the shared nature of our chemistries. Dole used to say that it took 10 years to learn anything and then another 10 to know what to do with what you learned. Occasionally he would give me a sheet of handmade Fabriano or Magnani paper and I kept it like a treasure, never thinking of using it in my work. From 1974 - 1980 I used Arches or Rives cover, and inexpensive varieties of hosho paper, which I would stain, sand, drench, saturate with pigment, tear and layer. I constructed collages that connected me to rhythms of the land or the cadences of jazz.

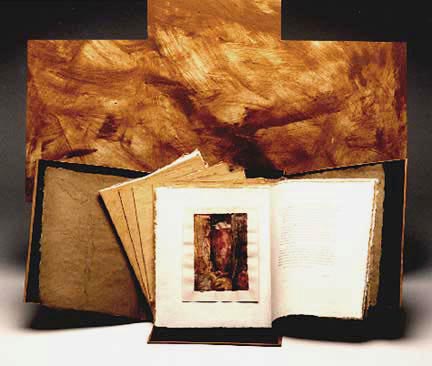

Until 1978, largely through my own ignorance and lack of exposure, I was unimpressed with most of the hand made paper I had seen. It looked like cardboard-thick, super absorbent paper toweling, often tinted a peachy color with all sorts of debris placed into it. Chuck Hilger first introduced me to making paper by hand in his Santa Cruz, California studio – as a keen observer but not as a participant. He invented a vacuum press that allowed him to cast giant snow white sculptural pieces. The success of the press enabled him to travel and exhibit worldwide until 1990 when he sold his equipment and devoted his energies to directing the Museum of Art in Santa Cruz, California. "I could do in 15 minutes what used to take me 10 hours," he told me, recalling his invention, "and I rode that pocket-rocket for as long as it was there. I made lots of work, met amazing artists and had a ball." Although we talked about collaborating, I never had the pleasure. In the early 80's I attended a small workshop held at the home of Harry and Sandra Reese. The Reeses make rag papers onto which they print exquisite letterpress and hand-bound editions of poetry and prose under the imprint Turkey Press. Harry invited author and paper artist Sukey Hughes, who was living in Santa Barbara, to teach the workshop with him. Harry taught Western and Sukey taught Asian techniques. In the ReeseÍs backyard we set up vats and boards for making and drying sheets of paper and this was the first time I actually got my hands wet. Sukey had gone to Japan in Summer 1969 as a writer. She was fascinated with Japanese culture and wished to write about papermaking. "I was approached by a villager who acted as guide and translator, leading me to the home of Gotoh Seikichro, a living treasure of this particular prefecture. Through the interpreter I asked if I could come back and interview him about his craft. Mr. Gotoh said, 'Come back on Monday and we'll make paper together,'" Sukey told me. "I was nervous about this because I only wanted to interview him but figured I could straighten that out on Monday. But when I arrived on Monday the town newspaper was there to photograph me, the foreigner, beginning an apprenticeship with their treasure – and there was no way out, I had to do it. So, it was a mistranslation, a misunderstanding that led to me working for eight years on my book and learning how to make paper for the next nine months!" The result was Hughes' publication of the landmark text, Washi: The World of Japanese Paper, 1978. Working with Sukey permanently changed how I related to my materials. Time slowed down. My exuberant expressionist tendencies had to make room for carefulness. We boiled the fibers, cleaned and pounded them into a pulp, the air redolent with a caramelized, woodsy scent. Before I pulled my first sheets of gampi and mitsumata, I watched the clouds of fiber disperse in a vat of cool water, how they spiraled like weather patterns when my hands stirred counter-clockwise to distribute the flocs before dipping the mold into the vat. I felt the smack of a vacuum as the mold broke through the surface tension of the water. I brushed the sheets gently onto lightly waxed plywood boards, and in this fluid state they all but disappeared into the wood. Later, as I peeled the bone dry paper off the board and lay the imperfect sheets in a humblingly small pile that represented three days' work, I gained a new respect for papermakers and determined to learn more about the art. I came to understand that my passion rests with the way an idea is traced – the process, the unfolding, the return. While forming sheets, my mind seemed to empty out as I moved the screen level with the earth, in all four directions, mesmerized by the waves of water striping one way and then the other. During this time I knew I was working on the silent underpinnings of a future series, getting to know the sheet as it was forming. Each sheet of paper I made was imbued with the memory of its making. As I laid them out on the floor of my studio, my preferred working place, I discovered that each sheet, flawed as any amateurs', had a voice, which often stubbornly defied being painted on. I decided to incorporate my paper as single elements into collage, feathery deckles and all. Dole died in 1983 and I inherited several sheets of his paper and jars of powdered pigments. It wasn't until 1992 that I knew what to do with the paper, and not until 1997 that I was able to use the pigments. In an exhibition in conjunction with a Dole retrospective at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (1992), I made a series called Dialogues in which I used Dole's papers, the papers I had made by hand at Sukey's studio, plus paper my daughter, Sienna, had found and sent to me her first year away from home at Brown. Dialogues is about silent conversations and the letting go of precious materials. The contextual significance of these papers far outweighed their aesthetic value. By expending these materials, something was released in me that allowed me to start using beautiful papers more generously in my work. I remarried in 1989 and began traveling extensively while on assignment with my husband, photographer Macduff Everton. In México City I met Juan Manuel de la Rosa, who was making paper from indigenous materials, and who kindly provided me with a source for cochineal and indigo. I sought out new sources of handmade paper, particularly as I traveled to India, México, Nepal and Japan. Hiromi Paper International in Santa Monica and Dieu Donne in New York are my favored US sources. In 1993 on assignment for Outside magazine, we spent a month in India, visiting the monasteries of Sikkim during Tibetan New Year. Monks dressed in blood red and saffron robes blew on trumpets as long as a Lincoln. The air was thick with chanting. Buddhist prayer flags punctuated the Himalayan sky. I came across a handicrafts shop in Gangtok, Sikkim, where I spied paper with silken threads chopped into stationery sized sheets. With the help of our guide, Pema, I was led to the papermaking workshop where 10 women, arms graced with gold bangles and feet kept dry with Wellington boots, were making paper. Pulling at the ends of my hair and the frayed edge of my shirt, I tried to get across to them that I wanted paper unstripped of the deckled edges. Two weeks later I was presented with 200 sheets of silk and cotton paper with a deckle I can only call Rastafarian. This is one example of how a specific paper determined my work. I felt I had to use the entire, abundantly fringed sheet, which I colored with crushed cochineal and into which I imbedded a small watercolor, edged with gold. I called the series Kama Sutra. I continued to work with Sukey, who had moved to New Mexico, whenever I wanted to make paper. It was with great pleasure that I was able to make a small contribution to the art of making paper by focusing on the one most tedious aspect of the process – pounding pulp. Sukey, a calm, meditative woman, knelt on a shoji mat before a small bread board with mallets in each hand. Before joining her, I put on a cassette tape and a flood of Spanish Flamenco music filled the room. We pounded with a staccato-percussive fervor to the exhortations of Celia Rodriguiz and the strumming of Manitas de Plata. Pulp never got such swift and boisterous attention! For me, making paper for me was never an end in itself. My paper was flawed, but the deformities were an asset because surface texture played such an important part in my collages. I had often used the metaphor of shedding and growth in my writing and painting and this gave me an idea. Snakes shed their skin each Spring. A biologist friend saved some skins for me and I brought them, in 1994, to use in making paper. At first I frustratingly tried to position them in the screen, but they would not stay in place. Instead I simply allowed the skins to find their own place, as I dipped the mold twice into the vat. I had no idea what my end product would be. At that moment I was purely a conduit for the paper that I made. This series confounded me. I am trained to "do something" to the paper but in this, the paper is the piece. Certain places Macduff and I have visited touched a core in me and many painting series have been influenced by them. However, I felt torn between traveling and being in the studio. It was impossible to do any work while on the road. Journal notes became the thread that linked me to the studio. Finally it dawned on me that I could work an accumulation of writing and images into book projects. My first editioned book (simplemente maria press) was Old Marks, New Marks, a chapbook of writing and painting that linked my work to one source of inspiration, the Paleolithic images from the caves I had visited in the Dordogne, France. With help from Sandra Reese, I constructed clamshell boxes using cloth and paper over boards. Inside I placed an original handmade paper collage and the chapbook I had designed on the right (edition 40). Only with my second limited edition book that I learned about the production aspects of paper making. A three week trek through the volcanic landscape of Iceland inspired two painting series and a book of poetry and prints.

|

|

|

|

I used the jars of pigment I had inherited from William Dole to make large paintings on Stonehenge paper in which I bombarded the surface, sprinkled with pigment, with a watery binder – my own studio-sized volcanic explosions. I made contact monoprints on handmade kitakata paper from these larger paintings and coupled 11 images with excerpts from my journals as a gift for my husband. This unique book was the basis for Island: Journal From Iceland (edition of 60). I needed to find a translucent paper that I could print on but which was not brittle like vellum. I wanted each folio to have text printed on the front with the image showing through from the inside page. Inge Bruggeman, printer and bookbinder, agreed to print the text and introduced me to a young graduate student, Rie Hachiyanage, who had studied with Timothy Barrett and was then a student of Harry Reese. Under less than ideal conditions and with fervor, dedication,( and strong forearms), Rie made 900 sheets of beautiful overbeaten abaca paper. Like an iceberg, Island: Journal From Iceland became larger and more costly than I had envisioned, and people involved really went the extra mile. In order to make the paper for this project, Rie encouraged the Art Department to install a filtration system and purchase materials for drying large runs of handmade paper. This equipment enhanced the departmentÍs burgeoning book arts and paper making programs. Rie was helped by Gail Berkus, who was learning how to make paper and who had helped me construct the Old Marks, New Marks boxes, as well as the chemise covers for Island. Old Marks, New Marks provided an entree into yet another book arts project. The French Minister of Culture responded to my chapbook by inviting me to visit the real cave at Lascaux in May 1997. (I had seen the well-constructed facsimile in 1995.) In the real cave, the color was vivid and fresh, surpassing all of my expectations. Animals seemed to bleed out of the walls. Reds and ochres wove in and out of tarry black outlines. Inside, I felt as if I were within a steep-walled clay vessel, gyring on a potter's wheel. I made a series of improvisations in ochre pigment burnished onto handmade Torinoko paper based on the plan-view map of the cave. I also applied ochre over Torinoko paper to construct the cover for my third book, Scratching the Surface: A Visit to Lascaux and Rouffignac. I produced a unique book consisting of six folios of handwritten text and six dry pigment paintings on kozo and abaca paper, half of which was pigmented with ochre. Using the same pigments as our forbears painted with more than 20,000 years ago was like rubbing shoulders with an ancient past. Based on the unique book I produced an edition of 10, each containing six original paintings. Scratching the Surface and Island were part of an exhibit, "Artists on the Road: Travel as Source of Inspiration", curated by Krystyna Wasserman at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, October 1997 - May 1998. I felt that this would be an intimate enough project that I could do all aspects of the book myself, save the letterpress printing, which I left to Inge. I had tried to produce the paper at home, using abaca fiber Gail Berkus and I had beaten in her Hollander. The porridge-like slurry took 20 minutes per sheet to drain! It puckered, wrinkled, and caught the rain of an endless El Niño storm. I just gave up and let it happen. I made the weirdest, rain-spit paper I'd ever seen, yet there is an uncanny beauty to it. I am using it to make a series of drawings based on Cycladic figures. This experience is a lesson that some of the most interesting art can come out of mistake and mishap. While I could use it for other projects, this paper would not do for making my edition. I needed a work space that was equipped to manufacture and dry uniform sheets. I reserved three days at Dieu Donne Paper Mill in New York City and worked with Pat Almonrode. Pat prepared a mixture of abaca and kozo pulp to my specifications which I then pigmented, using a marvelous color-testing method of concocting a mini-screen from a plastic deli container. Pat fitted an 18" x 24" mold with a foam-core divider so I could pull 2 11" x 17" sheets at once. We found a rhythm of working, one pulling and the other couching, then switching, that was unbeatable. We made over 300 sheets in two obsessive days and I had a third day to experiment with pulp painting and free-form construction of paper pieces. I approach each project knowing that the material itself will seduce me, and that the methods I employ, whether doing production work or experimenting with individual sheets of paper, will help to define and determine the steps towards a finished piece. The idea of working solely with pulp to make art now fascinates me. I will return to Dieu Donne this Spring, again reminded of DoleÍs dictum about the time it takes to learn. Every time you make paper is like the first time you make paper, but when you are in love, twenty years passes like an instant.

© Copyright Mary Heebner for Hand Papermaking Magazine, Summer 1999 To see more paintings on handmade paper: Papermaking photograph of Mary making paper © Larry Mills |

|