| Artwork | Index | Editorial Writing | |

| Books | About | Links |

| Mary Heebner |

|

Travel Holiday |

|

|

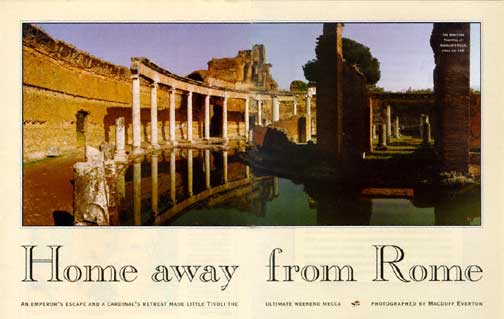

IWe are the first visitors on this early Spring morning to arrive at the ruins of Hadrian's Villa. The little snack bar and the cement parking lot are empty. We walk through the entry way, a corridor of tall, fragrant cypresses that slice through the remains of an ancient olive grove. The olives impart a rich musty odor which mingles with smells of freshly cut grass. My senses pivot around a feeling of time-traveling, and as we walk toward the ancient structures, our chatting thins out to a smooth silence. What was the Villa like back in Hadrian's day? All that we see is the residue, the bare bones of an earlier extravagance and splendor, yet it takes on an uncanny beauty and richness in the morning's half light . In the distance we can spot the aggregation of arches and domes that are the ruins of the library, baths, colonnades and theaters. Like a great earthen vessel cracked open to release the spirit contained within, the roofless, curvaceous brick ruins of the Villa rise upward out of the landscape. The halved and vaulted remains of overarching domes cup the sky. Within the walls graceful and delicate hairpin-shaped arches frame the deep indeterminate space that is colored olive, rust and cerulean. We pull together a simple picnic of proscuitto and gorgonzola pannini for breakfast and are immediately |

greeted by a coterie of dogs anxious to guide us through the ruins if only to catch a shred of meat or bread as compensation. We walk over to Belvedere Plaza, a rectangular walled garden with a large pond at its core. Ducks glide on the water. One of the dogs strains toward the ducks and breaks the silence with his barking. We make our way toward the Canopus, with its elegant pool, at the further end of the 180 acre site. In the aftermath of some recent excavations and repairs, plaster copies of conventional Greek garden statues unearthed elsewhere in the Villa are now placed on pedestals somewhat claustrophobically around one end of the simple pool. Reflective pools were created, it is said, out of a desire to observe the star-filled heavens at nighttime. The incomprehensibly vast Universe contained within this cool space would invite dreams, desires, and musings. In hazy daylight, these statues mirrored in the water's surface acquire a transitory softness. Their Narcissus-like reflections are occasionally stirred into stripes of white across the blue-brown water as ducks, birds and insects now lay claim to this long abandoned habitat of dreaming. A tour group with an English speaking Italian guide arrives. People cluster around the pool, filling in the gaps between statues, creating, from our perspective, a visual pastiche of humankind among the lesser gods of the garden. The tour guide obliviously offers up bits of historical data to this rather remarkable audience. Hadrian built Villa Adriana twenty kilometers away from the center of Rome on a site previously owned by his family. Begun in 126 AD. and still undergoing improvements when Hadrian returned from the last of his travels in 134 AD., the Villa was to be home to his collections, libraries, musical instruments, statuary and beloved objects which he spent a lifetime gathering. The Villa was to be a synthesis of architectural styles and included a Greek and a Latin theater, an "Academia " emulating the famous Academy of Athens, circular galleries of Egyptian origin, the caryatids in the Canopus based on the Temple of Serapis complex near Alexandria, mosaic work, and splendid Oriental detail. It was set amid spacious, meticulously landscaped gardens. Large reflective pools invited contemplation and fantasy. Hadrian wanted this miniature empire to be his final resting spot , but ill health often forced him to seek the warmer climates of the South. Hadrian was a musician, poet, and architect, as well as a statesman. In the four years that he enjoyed the Villa, it was alive with theater, dance, music, opulent feasting and gaming, however, he would often withdraw to the Teatro Maritimo, a circular house surrounded by a moat inside the outer walls, where he could read, write poetry and relax in privacy. The Emperor was born in what is now modern Spain. He was

educated in Greece and Rome, gradually won favor with the ruling family,

and was formally adopted by the Emperor Trajan on his deathbed in AD.

117, thus securing for himself the coveted position of Emperor of Rome.

He perceived the world as his classroom, his chessboard, his canvas,

his garden. Although Rome was the center of his universe, his travels

extended from Britain to the lands that ringed the Mediterranean. |

|

| Hadrian was a man of passion, sensuality and wit. He loved music, philosophical and religious debate, storytelling, hunting and gaming. He elevated the arts and architecture to a status comparable with the golden age of Augustus, creating entire cities, navys, and temple complexes, that he named after beloved friends, He was loved by many, often deified by those living outside of Rome, who knew him only as a graven or sculpted image, a distant force whose Imperial decisions substantially altered the course of their lives. Hadrian saw himself as a peace-loving, protective, and civilized man, burdened with a restlessness that would attend him throughout his life. He was compelled to bring within the folds of his Empire everything new and of interest which he discovered during his extensive travels, like some crazed shepherd forever introducing new stock into his flock. In Rome, Hadrian built a new temple on the site of the ruins of the old public baths.

|

|

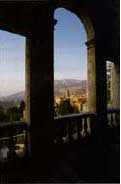

Little remained of the old structure, which was destroyed by fire, but the original marble plaque bearing the inscription M. AGRIPPA L.F. COS TERTIUM FECIT ( Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, Consul for the third time, built this). The Pantheon, a temple to all gods, gave expression to Hadrian's vision that all the gods were manifestations of a singular but complex cohesive energy. The design made reference to early Roman huts with their smoke-holes in the center of the roof. It opened like jeweled eye to the sky in harmonious proportion (it's height being the same as it's diameter) that revolutionized architecture for it placed emphasis on the richly decorated walls and coffered dome of the interior, instead of the exterior, which was left simple and unadorned, except for the original plaque crediting Agrippa. Hadrian refused to have his name inscribed on the Pantheon or on the many other architectural projects he designed throughout his lifetime. Even pre-dawn traffic clicks along at a frenzied pace in downtown Rome, so the peacefulness of the ruins of Villa Adriana is welcomed and causes me to wonder how Hadrian must have longed to escape the city and all his Imperial duties -- to walk beneath the elegant archways, share some bread and wine with a lover, nap by the still pools of the Canopus, and enjoy his final, most personal architectural endeavor undisturbed. Little is known of the Villa's use after the death of Hadrian in AD. 138. The site was looted and plundered through the years, and many of its treasures were destroyed or dispersed to various private and public collections throughout the world. Supervised scientific excavation began in the late nineteenth century, and Greek made statues which Hadrian imported as well as busts of later emperors have been uncovered. During the Renaissance, there was a revived interest in classical antiquity, and Villa Adriana became the model for the villas built by that era's royalty, papacy and upper classes, creating a tradition of elaborate and fanciful villa gardens throughout Italy. The day heats up and the parking lot is full. We smell pizza baking and hear the hiss and gurgle of the espresso machine among sounds of English, Japanese, Italian, and babies at the snack bar. It's time to leave. I imagine the spirit of Hadrian retreating to Teatro Maritimo to seek shelter from the crowds, and as we exit the grounds, we decide to head through the town of Tivoli , to the hilltop of the Villa d'Este, ten minutes away. "Valle Guadente" translates as the Valley of Revelry. Its name meant good luck to the eccentric Cardinal Ippolito d'Este, who chose this site in the mid-1500's for Villa D' Este, an elaborate Renaissance villa and garden complex. As the son of Lucretia Borgia and Alfonso d'Este, this extravagant project more suited his tastes than settling into the rather austere Benedictine abbey which was to be his quarters as the newly appointed Governor of Tivoli. d'Este worked with the architect-artist Pirrio Ligorio and architect-engineer Alberto Galvani to divert the forces of the Aniene and Herculenean rivers into a splendorous puzzle of waterfalls and fountains in a three-tiered garden with connecting stairways. The technology alone is an engineering coup. The small town of Tivoli was in for a splash. One whole district was leveled to make room for the spacious grounds, and the entire project plowed ahead at a pace that can only be sustained with unlimited money, and the absence of a city planning board, budgetary and review processes. The terms bubbling with laughter and brimming with joy might have found their roots in these gardens. Weekenders from Rome, as well as travelers from abroad, who descend into the noisy cacophony of the fountain-filled gardens seem to awaken to the spirit of playfulness, childlike mischief and unabashed laughter. The place buzzes with delighted visitors engrossed in watching the upward surge of water from fountains, smiling at the milky spurts of water flowing from the breasts of sphinxes and goddesses, and discovering Neptune's visage veiled by an avalanche of water from the many-tiered fountain that bears his name. Traditionally a garden is a place where human endeavor takes the vastness and wildness of nature and creates an organized space, a fragment of structured calm carved out of the largesse of natural life. In the Villa d'Este, amid the sound of rushing and cascading falls, water passes through rings of carved stone and limbs of mythological deities. Outside these garden walls, water damage from flooding and runoff in Tivoli was often devastating. However, within the garden, water became the medium through which a virtual playground for the 16th century elite was created. |

|

Today mosses and maidenhair ferns blanket the stone figures of nymphs pouring water out of pear shaped vessels and obscure the monstrous visages of water-spitting chimeras along the Walkway of One Hundred Fountains. "Something magical exists here. Perhaps it's that we ourselves are comprised of over 90% water, and that once our fluid nature comes into contact with such overwhelming ebullience, the desire to merge overwhelms us and "leaks out" in the form of candid laughter, kisses, chit-chat and bursts of energy. My companion and I indulge in all of the above, clipping up and down the many tiered steps, loving the occasional sprays of water an afternoon breeze might blow our way. Hadrian's Villa seemed most approachable in the quiet solitude of an early morning, but the gardens of the Villa d' Este seem to come alive when human voices mingle with the sounds of gushing water. Now all this gushing has given us quite an appetite! We wind down the hillside and head straight for a trattoria spotted earlier. At Franco e Emma's (Vial del Tartaro 82, tel. 0774/ 530603 - open every day but Monday) hunger has won out over propriety. No sensible Italian would be dining this early. Nevertheless we are politely greeted by a young waiter eager to practice English. The room is empty, the tables are set, and fresh bread, olive oil spiced with garlic, and crisp cool vino di tavola keep us occupied while our waiter attends to preparing for this night's crowd. Our timing mirrors the day's excursions -- this interlude of quiet dining is to be as short lived as our solitude at Villa Adriana. By eight P.M. there is not an empty table in the house. Laughter, singing, conversations in Italian that defy the speed of sound, pizza after pizza after pizza, liter after liter after liter---the joint is jumping. Our meal progressed from a seafood antipasti to homemade linguini, more vino, fresh grilled fish, assorted fruits and cheeses concluding with a steamy espresso and an amaro, an herb-infused liquor, bitter-sweet to the taste and, we are told, good for the digestion. On a much needed after-dinner walk, the highway flickers with the steady pulse of headlights, and taillights redden the distance. Even in Ippolito d'Este's time, Hadrian's Villa was an abandoned ruin, over fourteen hundred years old. Over four hundred years have passed since Popes and dignitaries were entertained at the Villa d' Este, and it too is slowly making its slip back into the earth, as the vines and mosses eat away at the carved mythic and anthropomorphosized stones. Maybe the reflecting pool, that habitat of dreaming, is effecting me, for the headlights this evening now seem to me like so many stars in the night.

|

|

Copyright © Mary Heebner 2000

|

|