| Artwork | Index | Editorial Writing | |

| Books | About | Links |

| Mary Heebner |

|

Conde Nast Traveller UK |

|

|

I thought that Day Glo colors were a fashion aberration of the 60's until I visited the tropics. The jungle is florescent, abloom with the unmitigated shock of color. Exchange Turner's palette for Rousseau's, add the perfumes of flora, rain, and salt, stir in a ragout of hoots, howls, purrs and murmurs, and you have Pura Vida - pure life. That's Costa Rica. Pura vida is the Costa Rican equivalent of ciao, a greeting, an adios, a blessing. "How's it going?" "Pura vida". They also use an endearing diminutive form - just a momentico, or, I'll have a cafetico, and they call one another, simply, ticos. Less than half the size of Ireland, Costa Rica is the runt of the Central American isthmus, the serpentine landform that joined North and South Americas through volcanic eruptions millenea ago. Over 400,000 indigenous people lived here when Christopher Columbus claimed this land as a "rich coast" for the Spanish Crown in 1502. By 1589 less than 20,000 lived here, and many of them were exported by Spain to Peru as slave labor. Spain largely ignored this difficult, poor, mountainous plug of land, and, like the middle child in a large family, it was left alone, save for a handful of hardy settlers, developing an independant spirit at an early age. |

Costa Rica is not a typical Banana Republic. Its one of the oldest democracies in the Americas. In 1948 it did what any other Latin American country would consider lunacy – it disbanded its armed forces. The cream usually skimmed off the top by the military instead recirculates into the economy. Costa Rica has a 94% literacy rate. In 1987 its President won the Nobel Peace Prize. You can even drink the tap water. There are two seasons in Costa Rica, the wetter "green season" from May through October, and "summer". Thankfully, Costa Rica's summer season overlaps our winter, lasting from November through April, which gave my husband and me the chance to jump ship on foul weather and get out the sunscreen. We came seeking sunshine. In addition, we got an education in biology. If all learning could be so painless. |

|

|

The mysteries of botany and ornithology had even the most urbane travelers gawking with wonder at the natural world. We saw soldier termites repair a break in their elaborate tunneling network in minutes while sloths took 20 hour daily naps in trees above. Acacia leaves fold like a prayer when touched, and lizards walk on water. Fence posts sprout in the rich wet soil and bird-sized iridescent blue butterflies flit by like an illusion. Getting anywhere in Costa Rica is a schlep, so we packed light, dressed informally, and Horizontes Nature Tours took good care of us. Their drivers proved excellent historians and guides. We found Ticos to be proud of their country, articulate and informed. They steered us through the details so we could relax. We chose to avoid the grit and concrete of San Jose, instead, spending our first nights viewing the city as a basketfull of lights |

|

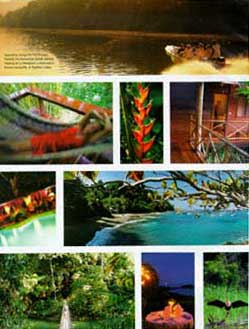

from our private patio terrace at Xandari Plantation in Alajuela, designed by California architect Sherrill Brody and his artist wife, Charlene. Although just minutes from the airport, this exquisite and thoughtfully crafted cluster of 16 villas secluded in the middle of a working coffee plantation offers privacy and an unparalleled view of the valley. In late afternoon we walked past the lap pool and the tropical gardens onto a mulch-softened trail through an orange orchard heavy with blossom and fruit. Past a grove of golden bamboo, we crossed a creek where a mottled sprawling higueron tree towered above the rest. Its exposed roots braided down the hillside and crossed the streambank forming a natural bridge through which water fell into a fern-lined swimming hole. I bathed in the cool, soft water. My hair dried to a silkiness I've rarely felt after this volcanic coldwater rinse. Dawn came just before six. Breakfast, including the freshest squeezed orange juice, was brought to our room and we then left Xandari for Tortuguero National Park. It took hours on a bus and boat to arrive, but it was worth it. Feeling the spray against my cheeks and the sun on my back, I forgot about the bus ride, enthralled with what would become an endless parade of wildlife. On the bank a glorious ahinga, spread its wings, patterned like intricate beadwork, open to dry. In the 1940's, a family from San Andres, Columbia came here to hunt turtles. In the 50's a lumber company clear-cut the entire area, selling pulp for press board. They built a canal paralleling the rough Atlantic ocean to transport their cargo fromTortuguero to Puerto Limón. Turtle hunting was eventually prohibited and the area protected. Our home for the next three days was one of the newest lodges on the canal. We exchanged timid smiles and a few words with the others in the boat, which developed into a friendly ricochet of English, Danish, Spanish and sign languages, as our group, led by Sylvia our guide, motored toward Pachira Lodge. Pachira is named after a flowering tree that blooms only once at night and emits a wild perfume. Our room was one of four in a raised and screened-in bungalow. There are nine such bungalows connected by wooden catwalks and a central commons. After an agreeable dinner we slipped away to sit in wooden rockers on the dock and watch a tortoise shell sky shift under a giant moon. From the nearby cicadas to the low moans of howler monkeys lay the distance between us and the forest. We woke for the sunrise canal trip into the forest. The first light here is so tantalizing that I'm setting new personal records for getting up before the sun. The far bank was a black smear. Then, an iridescent pink illuminated the spaces between the trees as the sun rose. From beyond that bank we could hear the constant purr of the Atlantic. In two hours we saw osprey, egrets, yellow-crown, green-backed, tiger-striped and great blue herons, ahinga, jacanas, kingfishers, toucans, parrots, oropéndolos, woodpeckers, tiger striped heron, flycatchers, slated tail trogan. Iguanas, three cayman, howler, and capuchin monkeys, sloths, basilisk lizards. And more. The idea of devoting time to spotting little brown things in the trees suddenly became fascinating. Birders tallied the lifers they spotted. In Spanish and English Sylvia enriched what we saw. The female jacana lays her eggs and several males each make a nest for just one egg, which they guard and care for until it leaves the nest. " One of the rare, feminist birds of Latin America," she quipped. We steered away from the more open, previously cultivated secondary forest, into the primary forest. My first thought – The African Queen. Caño Palma was dark, thick with roots and lianas draped from heavy branches. Monkeys racketed from the trees, logs jutted out like crocodiles into a river dense with flotsam. Haunting. The black river was a mirror reflecting the palm fronds and tree logs, creating the beautiful symmetry often seen in native design. Diamond and chevron motifs must have come from people living at the edge, between water and forest.

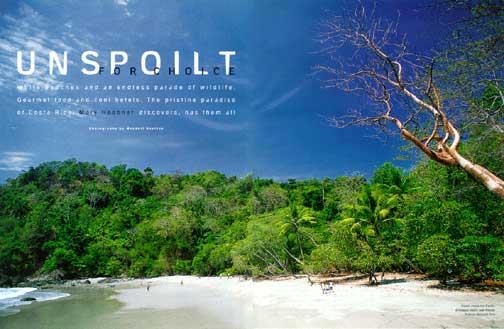

Horizontes arranged a charter flight to the Pacific coast – expensive but more timely for the distance we wanted to cover. An hour flight saved us two days' road travel. Lifting up, the forest gave way to quilted patterns of cultivation, until we crossed the pinched tarpaulin of volcanoes that bisect the country. Tracing the foothills of the Talamanca Range down to the white sand coral beaches of the Pacific, we landed at Quepos and Manuel Antonio National Park. A waiting van took us a short drive to Makanda by the Sea, an oasis of blues and white in a rainforest setting, well above the strip of snorkel rental shops and pizza huts that line the road. I took a cool swim in the infinity pool that teases the horizon line and then walked to the beach, following the dirt path down to the shore. Manzanillo trees scallop the edges of the hot sand in shade. I walked toward the entrance of Manuel Antonio Park, stopping to watch surfers ride out a few sets at Playitas break and Entre los Rocas. Manuel Antonio was designated a park in 1972, preserving it from hotel stripitis that threatens this area. We arrived early, waded across a shallow estuary pool and joined tourists and Ticos already in line with picnic coolers. Playa Tres was the most popular destination with a gently sloping swimming beach- other beaches have quite a rip. Dramatic headlands face offshore islands and beaches abut forest rich with birds and wildlife. Unfortunately, tourists have fed the capuchin monkeys and they have become aggressive pests. Throughout Costa Rica, we cringed at people feeding wild animals and wished they would think about the consequences of turning hunters and foragers into beggars . |

|

I didn't expect gourmet dining in Costa Rica. However, Roger Campos, a young Quepos-born chef atat MakandaÍs Sunspot Grill stunned me, considering the shoebox kitchen literally beneath the small patio dining area by the pool. From this mini-inferno Roger conjured green-lipped mussels in wine sauce, radicchio, arrugula and friseé salads, prawns in ginger with grilled vegetables, and rack of lamb. The next night we stayed in the oldest luxury hotel in Quepos, La Mariposa, just down the road. With its Spanish Colonial villas, panoramic view of the beach and outlying islands from the dining terrace, it is geared for doing absolutely nothing and cried out for cocktails at sunset. Local waiters and taxi drivers suggested Jiuberths, promising the best seafood in Quepos, and my experience has been to trust such advisors. We weren't disappointed. It was a good sign that most of the diners were Ticos. An enormous mixed grill platter between us and two corvina and camaron ceviches, a carafe of decent Chilean wine, and we were sated, and delighted by the decor – Sargasso Sea meets the Ancient Mariner. We took a 30 minte flight to ecape a day long teeth-rattling drive from Quepos to the Osa Peninsula. To get to our destination at Drake Bay we boarded a small boat which sped down Rio Sierpe for an hour and then headed south another 11 kms skirting the Pacific coastline, to the Aguila de Oso lodge. "Una Aguila, por favor". I leaned against the polished armandio wood bar asking for the cold brew locals refer to by the black eagle on the yellow label. "The only way to do Costa Rica is to stay wet," pronounced the man in swim trunks next to me. "Inside and out," I said to him in Spanish and with that, instantly befriended Mario and his wife Patty from El Salvador. Dinner is served at 7 and guests share three large tables. The food ranged from succulent fresh bass skewered with tart slices of carambola star fruit, to overwrought dishes one concocts when trying too hard.

|

|

Mario's two other Salvadoran friends put Tito Puente on the CD after dinner and we broke into spontaneous dancing, barefoot on the wooden floor, redefining wildlife. A short boat ride from Aquila de Oso brought us to Corcovado National Park. A walk in the forest with our guides Eduardo and Olman was so rich in detail, texture, fragrances and living things (including ticks, bring repellent) that we walked at a snail's pace. A family of white-nosed coatimundi foraged nearby while monkeys trapeezed overhead. Fluted roots of massive trees like skirts twirling on the forest floor sheltered agoutis nibbling at fallen seeds. Bits of leaves strewn like confetti marked a leaf-cutter ants' Waterloo when attacked by a group of army ants. Eduardo pointed up saying, "When this butterfly emerged from the cocoon it was fat with fluid and it flexed a special muscle, just once, so fluid pumped into its wings like an opened umbrella, and then, it flew away". Walking biology. Costa Rica possesses a wealth of natural life, hosting more species than scientists have been able to count. Although only 5% of its primary forest remains, it is touted as a naturalist's paradise. However, ecotourism has become a much abused, poorly defined buzzword. Often tourism capitalizes on Costa Rica's assets without helping to conserve its resoures. The next day an Italian couple and we visited Caño Island, an hour's boat ride away from the lodge, to sun, hike and picnic. Protected as a native burial ground and sacred site, most of the island is off limits. Perfectly round basaltic spheres ranging in size from footballs to igloos, were found here, and no one knows much about the how and why. Caño is an evergreen forest with a fringe of coral beaches. Offshore the diving is excellent, but snorkeling off the beach is murky. The boat dropped us on a small beach by park headquarters. We were dismayed to soon see a swarm of boats from other lodges motoring in to invade our little paradise. We immediately staked a place away from the crowd for our picnic. Oddly, most of the guests hung together in the shade line of the almond trees, not unlike the hundreds of hermit crabs underfoot. On the ride home brown boobies hovered and dived, while magnificent frigates swooped in to steal their catch. The birds indicated a patch of ocean where a dozen dolphins ran running stitches through the Pacific. We flew back to San Jose and were met by a Horizontes driver who drove us to Tabacon Resort and Spa. At the northwestern skirt of the active Arenal volcano, this spa is fed by underground thermal springs. Dozens of pools and cascades ribbon through a lush, tropical garden. All the houseplants I have ever killed live robust, colorful lives here; heliotrope, orchids, canna, elephant ears, coleus, bromeliad, ficus, impatiens. I sat in a steamy pool of water, a gentle falls tickling my feet, watching a shocking pink dragonfly hover near a like-colored stalk of ginger. Arenal, swaddled in a boa of clouds, spewed steam into a blue sky and boulders the size of a lorry skid down this Victorian-necked volcano. I felt like Goldilocks tripping from pool to pool, some hot, others calm and tepid, and still others a bowl of froth at the base of a noisy cascade. Rising steam created a natural hothouse for plants and bathers alike. A cloudburst brought a warm rain that pummeled the hot vapors. The clouds yielded to aromatic, rainbow-stained air. An hour-long massage with essential oils, including a volcanic clay mask required a final soak in the pools before an al fresco lunch on the patio. All the usual stuff of paradise. Our last night in Costa Rica was spent at Finca Rosa Blanca. A mere fifteen minute drive from the airport, Rosa Blanca is a world unto itself. Like a multi-chambered clay vessel, Rosa Blanca is coiled, curved, eminently touchable, playful. Our suite, El Granero, had a small kitchen, two beautifully decorated bedrooms, and a metal curved balcony that bulged like the sinuous trees it overlooked. Owners Terry and Glenn Jampol moved from New York to perpetuate the dream that his mother began. Glenn fused his skills as an artist and builder with his mother's equally creative vision "to build a house with no square corners, filled with art". Terry is an excellent chef, culling from her organic garden everything from strawberries to asparagus and buying local fresh fish and meats. Every night the menu – for guests only – is a culinary E-ticket. When Glenn first visited Costa Rica in 1985 he returned to New York raving about "a beautiful country that has the nicest people on the planet." I tend to agree. Pura Vida. Copyright © Mary Heebner 2000

|

|