| I was

in the midst of Tahiti’s rainforest, submerged in a sea-green

universe. My eye began to discern the black-greens from the blue, lemon

or viridian greens, and the landscape shimmered. This was a mixing room

of colors, Paul Gauguin’s palette come alive. Everything was oxygen

and green, raw energy. I could feel it through my pores. Quite suddenly,

it answered one of the nattering questions I had asked myself, as a

painter, before coming here: Why, if French Polynesia is known for its

azure waters, turquoise lagoons and blue skies, did Gauguin compose

his paintings with eye-popping reds, greens and yellows set against

infinitely dark shadows?

As a painter coming to Tahiti for the first time, I had wondered why

so many artists and dreamers such as Gauguin, Hermann Melville, Fanny

and Robert Louis Stevenson and Jacques Brel, had traveled such distances

to a smattering of islands in the South Pacific. Perhaps they wanted

to be awakened, as did I. I wanted to be startled by the light, the

noa-noa (or fragrance), the colors and set out for Tahiti during the

rainy season to experience it in its time of lush, wet renewal.

I had started where most do, in the capital of Papeete, a colorful cacophony

on the main island of the archipelago. At French cafes I sipped freshly

squeezed pamplemousse juice and ordered from chalkboard menus. On some

mornings, I would walk to Le Marche, a two-storied covered market that

is a sea of colorful fabrics, of hats and purses woven from palm, of

fish, meats, produce and spices. In one corner, big-armed women set

up their tables with bright calico cloth then a layer of newspaper.

On this visual collage of text blocks and Matisse-like flower prints,

they carefully placed pyramids of red, green and yellow fruits and vegetables,

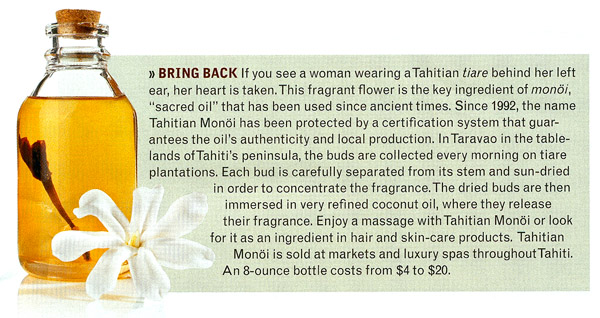

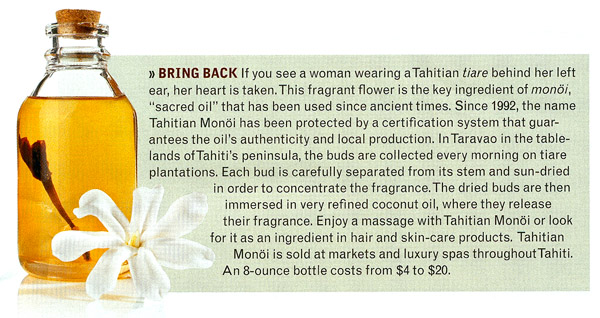

or fragrant oils and shell work.

In a shop within Le Marche, called Fauura, I met Rehia Raveda, who showed

me pieces of mother-of-pearl jewelry. Her hand-stitched necklaces begged

to be touched. One looked like snake scales, and the grey mother-of-pearl

revealed undertones of violet, green and rose. Her work was superb,

carefully crafted objects of beauty, using the simplest material: fiber

and shell. This necklace celebrated the island’s natural materials,

changeable skies, the polish and chime of running water. As I touched

it, I longed to get closer to the sources of this handiwork, and so,

using Gauguin’s journal Noa-Noa as my guidebook, I decided to

set out south from Papeete which sits on the northwest coast to a spot

near the village of Paea that inspired Gauguin: the Grottos of Mara’a.

There, I climbed a flower-bordered walkway that led me to a series of

fern-festooned grottos fed by overhead springs, following the gamelan

sounds of droplets falling into the pools of the grottos.

Green is a color I rarely used. My favored palettes are of sea, sky

and desert but the verdant depths of the grottos beckoned me. It was

here, the painter wrote, that he swam further and further into the cave,

scaring his young Tahitian female companion who knew better than to

swim deep into the abyss. Perhaps, I mused, within that disturbing darkness

he was able to dredge from his imagination the deep timbre of his paintings

where shadowy figures haunt the background while the foreground dances

with happy color.

Three teenage girls arrived and somersaulted effortlessly into the black

waters, splashing all over my reverie.

Further down the road at Papeari is the Harrison Smith Botanical Gardens.

Entranced by its green, I stopped and sketched in a grove of mape (Tahitian

chestnut trees) with their sinuous exposed roots grasping like bony

fingers at the soil. “The Grandfather of Trees” is what

Harrison Smith called them. I’d read that he was an American physics

professor at M.I.T. who quit civilization as he knew it in 1919. Smith

imported more than 200 species such as the fruit trees mangosteen, pomelo,

rambutan, and many ornamental varieties, creating his own garden of

Eden around the grove of mape.

The gardens only whetted my appetite for greenness, so the next day

I signed on to see the wild, rainiest part of the island, with Kevin

Renvoye, a guide for Tahiti Safari.

From Papeete, we drove east along the northern coast, passing black-sand

beaches where surfers and boogie boarders rode head-high choppy waves.

We turned off the circle road at Papenoo and climbed in the direction

of the volcano’s caldera. The Papenoo Valley, Kevin told me, averages

more than 216 inches of rainfall a year. The caldera itself has long

ago eroded but what remains are lush amphitheater-shaped valleys steeped

in every imaginable wavelength of green. More than 1,000 species of

plants thrive here and have provided Tahitians then, and now, with a

cornucopia of fruits, medicinals and building materials.

While barely slowing down the Jeep, Kevin reached his hand out the window,

plucked a yellow flower the color of fresh butter, and handed it to

me. “This is one of a few hundred types of hibiscus that is used

as a medicine for earaches and as a tea for flu; its bark is also a

common building material. But look at its heart.”

A blood red circle of color covered the flower’s innermost base.

“In a day, maybe less, the whole hibiscus flower will be streaked

with red. Young girls, when they want rouge, dab the red pigment on

their lips.” I, too, touched the color to my lips.

“Look here,” Kevin said stopping to show our group of six

a glistening bud from the wild ginger. “The natives used it as

a conditioner for the hair.” He squeezed it from the stem toward

the bud as if it were a tube of paste and a viscous liquid streamed

into my palm. I stroked my braid with the sap, feeling as if it melded

me to this landscape.

Continuing up the valley, we sighted a streak of pure power, the Vaiharuru

waterfall. Kevin translated for me: “The Noisy one, or as we prefer,

the Singing One.” I stepped out of the car, into the rainforest

to watch hundreds of falls polish the igneous rock to a sheen. They

ranged from thick and powerful surges to gossamer threads of white that

come and go with the rains, only emphasizing the scale and size of the

ridges that surround us. I was in a deep green bowl splashed with white,

watching Gauguin’s palette come to life.

Back in the Jeep, we navigated past dams, waterfalls and the Papenoo

River. Colors mixed before my eyes, from gray, to green to swirling

browns and indigos. Some of the waterfalls were now caramel colored,

heavy with soil from the rains. In moments, clouds wiped away whole

mountainsides, only to reveal a razor-edged peak rising from the mist.

I had expected the classic blue waters of Tahiti but realized that Tahiti

begins here at its fertile, volcanic center. This was the abode of fearsome

gods and fecund earth. This was what the painter had been grappling

with.

Kevin switched out of 4WD before we joined the main road. Mud-streaked,

smiling and zesty, I combed out my ginger-sap braid and my hair felt

like silk.

Back at my hotel, the Intercontinental Resort Tahiti, I made some small

watercolors. From my heart, colors poured down like rivers, churning

and gouging the paper, gleaming in every possible hue of island. My

pictures seemed paltry in the wake of the vivid experience. Yet I hoped

that these sketches would act as talismans of sorts, a source that I

could turn to later while in the solitude of my studio to connect to

this power I felt while in Tahiti.

Although I first learned of French Polynesia through the work of European

artists and writers, all around me were instances of native Polynesian

art, the most ancient of all perhaps being the art of tatau. My guide

Kevin had shown me the six tattoos he acquired over time at significant

moments in his life. Polynesians, once the world’s greatest navigators,

sailed the Pacific in hand hewn, double-hulled canoes. The long strand

of islands, archipelagos, and atolls were stepping-stones across a heretofore

unknown sea. They traveled light: their history, clan and personal narrative

written on the most ephemeral of parchments—their own skin. Even

though most of the ancient tatau narratives have been lost or forgotten,

there’s a resilient fusion of symbol and style, a blend of old

and new. I was determined to find a traditional tattooist, just to see

how Polynesians worked with pigments on skin and what the old designs

looked like.

I arranged to meet a tattoo artist who worked in the traditional way

on Moorea, a 30-minute ferry ride from Tahiti, separated from the mainland

by the dreamy-sounding Sea of Moons. As the catamaran ferry glided through

the reefbreak into calmer waters, I felt a twinge of the primal sensation

of sanctuary and refuge that the first navigators must have felt in

spades, as if the sea rolled out a gentle carpet to usher them ashore.

From the terminal on the eastern coast, I rode in a taxi north to the

Moorea Intercontinental on the island’s north coast. Along the

way I caught glimpses of the toothy mountain range, the gentle curve

of Moorea’s coastline. Palm trees rustled, kids at roadside stands

hawked pineapples, women in bright gingham hustled by on mopeds. Still

on Gauguin’s heels, I’d earmarked a passage in Noa Noa.

“The road was beautiful and the sea superb. Before us rose Moorea’s

haughty and grandiose mountains. How good it is to live! …The

landscape with its violent, pure colors dazzled and blinded me. I was

always uncertain; I was seeking, seeking.”

…Once I arrived at the hotel, I found the tattoo artist’s

grass-cloth and thatch shack between the pool and the sea. As I approached,

I could hear the thump of reggae beat coming from within. A handsome

man with hair neatly combed into a bun emerged. “Hi, I’m

James Samuela” he said, introducing himself. “My full name

is James Tamueratahiaheeatuahuuiti. I come from a long line of family

practicing the tradition of tatau.”

If syllables were shapes and vowels were details within those shapes,

I could imagine making a design from his name alone.

He showed me the tatau, a tiny comb with needle-sharp teeth that he

had fashioned from a shark’s tooth and tied with coir onto a smooth

stick. His client, a man in his 20’s from Suffolk, England, had

come to Moorea to have James cover his entire upper thigh with a traditional

design.

“We never even heard of Moorea, just looked up traditional tattoo

on the Internet, and so here we are!” his girlfriend beamed.

James dipped the tooth in dark ink and tapped to a percussive rhythm,

gently, steadily, and coincidentally in synch with the reggae beat on

the CD.

“Why doesn’t he bleed?” I asked.

“Ha!” he smiled, “With good tools you get your good

results…its all in here” he says pointing to his hand-hewn

instrument. “Man, when my dad used to tattoo it was gnarly, bleeding,

pain. I go slow, don’t draw any blood, it’s the light touch.”

Just as Gauguin voyaged here to re-create himself, he and this young

tattoo artist both shared a common bond, each in his own way trusting

these islands as a wellspring for artistic expression.

That afternoon on Moorea, as I was staring out beyond the reef from

my overwater bungalow, a white unarticulated, overcast sky turned grey

then mauve and when the sun shone from behind this scrim of weather

it glowed as lustrous as a black pearl. And in it, I saw a muse. She

summoned me to discover the mysteries of the black pearl.

Ron Hall, a laid-back Californian who sailed the seas, once crewed for

Peter Fonda, then settled in Moorea in the ’70s. He had an entrepreneur’s

knack for promoting the bounty and beauty of the sea, and his shop,

Island Fashions, in Paopao in Cook’s Bay is a popular spot with

locals and visitors alike. “I just want good pearls, and I want

good people to have my pearls,” he said with a twinkle in his

eye as he offered his customers in Island Fashions a 3 minute, 38 second

course in Ron Hall’s School of Pearl. I bit.

Pearls have been cultured for thousands of years, but not until ’70s

did anyone try to do it with the black tipped oyster cultivated only

in the atoll lagoons around Tahiti, the Tuamotos, Australs and Gambiers.

Ron apprenticed to one of these innovators. The pearls are not actually

black, but a sultry rainbow of peacock, bronze and pewter and the light

or luster seems to emanate from within. They caught my eye the way the

iris of an attractive person does, with a glint of reflection, warmth,

and mood. From Ron and his son Heimata, I learned that white pearls

have around 600-900 layers of nacre that form around a nucleus implanted

in the oyster’s gonad. What gives black pearls such depth and

reflective quality comes from 7,000 – 11,000 layers of nacre that

is laid down as the oyster turns the foreign-object nucleus over and

over, working hard to rid itself of it.

Once again, I saw unembellished materials in their pure form being transformed

into works of art. Naturally, by doing less, the result was ever more

refined.

Later that afternoon, it began to rain. A local woman in a yellow flowered

pareo stood just offshore holding a long cane fishing pole. The surf

just yards from where I sat, curled and broke, flashing a glimpse of

turquoise before collapsing into milk white foam, her sturdy body silhouetted

against the water. Nothing is ever entirely gone if you have eyes to

perceive it. Moments such as these captured Gauguin’s heart, as

evidenced by his paintings. Natural, not forced, graceful—all

these words synonymous with my experience of these islands. No wonder

that those who catch the enchantment keep returning.

Perhaps the inspiration Gauguin found here—his awakening—was

noticing the free flow between art and life. Life is art. Art is life.

Whether it was the revivified designs of tattoo, fabric of pareos, jewelry

patterns culled from the sea, or simply one’s wondrous body, art

becomes using what is at hand to make beauty palpable. Most importantly,

I realized, Tahiti offers a pace in which to savor life.

Back in Tahiti, the night before leaving for home, I watched a troupe

of dancers perform. Dancing, the art of movement, is a way of life here

that begins in childhood.

“My sister moved to Sydney, Australia,” confided a Tahitian

dancer as we watched the dancing. “She now thinks we’re

lazy but that’s how we are. We can sit and stare, and daydream,

without moving. That’s how you learn to live here. We go into

our dream.”

I recalled this conversation as I leaned against a post at the airport

simply watching the rain puddle on the heads of red ginger blossoms.

In my mind, I’d become one of Gauguin’s dreamy figures that

stared off into space. The fragrance, the noa-noa, had drifted over

me. Even before leaving, the longing took hold inside of me.

İMARY HEEBNER 2007 |